EssilorLuxottica – Through the looking glasses

Jul 2019 (€114)

EssilorLuxottica is no headline bargain (PE of 20-25x). However recent disquiet between its managers bought the share price low enough for us to take a look. We like what we found.

Introducing EssilorLuxottica (E-L), a new Holland Franchise:

- Pre-merger, E-L as independent businesses, had great track records of growth (organic and acquired) and high returns. Luxottica also had a maverick owner-manager at the helm (who today still owns 32% of E-L equity). After a multi-decade roll-up, this newly merged business dominates the eyewear market with quasi-monopoly positioning.

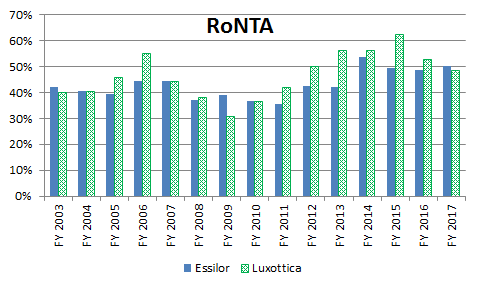

Fig.1: Excellent return on capital

Source: Holland Advisors

Source: Holland Advisors

- Eyewear is a very unique product that is both a medical device and a fashion accessory, both key for pricing power and margins. The product enjoys regular replacement cycles.

- The industry operates as an ‘agency model’, i.e. ophthalmologists are ‘agents’ in the eyewear buying process. We love the agency model (Howden/William Demant).

- Most health organisations agree that there is an under-served worldwide myopia “epidemic”. This means structural demand growth for the €100bn eyewear market.

- E-L is unique in the industry as it is vertically integrated with manufacturing, owned brands (Ray-Ban, Oakley, Varilux, etc.) and vast in-house retail and wholesale scale.

- Its unmatched scale brings cost and distribution advantages (aka ‘moat’) and an ability to invest in innovation. Its brands bring pricing power as likely will, in time, its merger.

..and yet, the regulators saw fit to approve the merger of the world’s dominant frame maker (Luxottica) with the dominant lenses maker (Essilor). We explain why later.

- Many blindly assume this market is ripe for e-commerce disruption and we address this issue head on too noting that the most prominent US disruptor has 90 stores!

- E-L shares trade on c.20x adjusted PE post synergies (c25x consensus 2019) – not the starting depressed multiple we normally like. Even so, given the low capital needs and excellent returns, our compounding model suggests, with plausible top line growth of 5% and some op leverage, the shares could still compound at c.11%. With reinvestment, that could stretch to c.13%. We are interested. A lower share price would make us more so.

In this note, we address five key areas of interest to us:

|

p.2 |

|

p.4 |

|

p.6 |

|

p.8 |

|

p.11 |

1. A quasi-monopoly in an opaque, unregulated, market

In this section, we make the following points:

- The global eyewear market is a fragmented and complex market

- Despite E-L’s dominance, this mega-merger passed anti-trust without conditions.

- In-house Optometrists play a key role as intermediaries in the eyewear buying process.

1. A fragmented and complex market

To bastardise Buffett’s aphorism:

It’s not that we like monopolies but we like the pricing power they bring.

Global eyewear is a fragmented and complex market that requires medical expertise (optometrist professionals who act as agents), technical lens laboratories, bespoke fitting, fashion brands, high-volume manufacturing and fast logistic services. One of the conclusions from the E-L anti-trust investigation was that the market’s opacity caused delays in the investigation i.e. that this is not a well analysed or quantified market (at least in the EU). To us as investors, this is a good thing.

We think E-L is a price maker, as befits a market leader that demonstrably understands the power of scale, distribution and especially brands (it either owns or has licensed the majority of luxury eyewear brands).

The global eyewear market is worth c.$100bn and is, by any standards complex in terms of distribution and fragmentation. The US retail eyewear market is dominated by retail chains (LensCrafter, Pearle Vision and Sunglasses Hut are all Luxottica owned) and the supermarket chains. In Europe, there are fewer similar scale chains – Specsavers, VisionExpress and GrandVision being prominent – but independent opticians are far more prevalent.

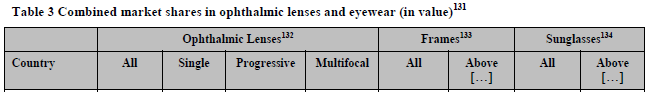

Fig.2 below shows the EU anti-trust assessment of E-L’s market share position in Europe before the deal was approved. As mentioned, in the fragmented European marketplace, E-L sells mainly wholesale, whilst in the US, E-L enjoys Luxottica’s longstanding position as the largest optical retailer[1] through its ownership of LensCrafter, Pearle Vision and Sunglasses Hut chains.

Fig.2: E-L: European pro-forma Market Share

![]() Source: European Commission[2]

Source: European Commission[2]

The phrase ‘complex monopoly’ has various connotations but we think EssilorLuxottica is at least a quasi-monopoly. That is, it has a dominant market position and pricing power which is reinforced by its brands, distribution channels and scale.

Specifically, the components of this quasi-monopoly are:

Lens Technological market leadership (8,000 patents)

+ R&D scale (3x nearest competitor)

+ Frames Brand Leadership (Ray-Ban, Oakley + Licenses[3])

+ US Retail chains scale

+ EU Wholesale scale (incl. Laboratories and STARS program)

= Moat (or quasi-monopoly)

Luxottica manufactured 83m frames last year and claims to have an ‘installed base’ of some 500m frame-wearers. Separately, Essilor claims that, of the 2bn people who wear corrective lenses globally, half have lenses made by Essilor.

2. So how on earth did the merger pass anti-trust?

In explaining the outcome, Essilor’s Head of Legal observed that “market dominance is not the same as ‘must-have’”: In other words, Luxottica (via Ray-Ban) ostensibly dominates the sunglasses market but sunglasses are typically a discretionary purchase.

We describe in section three, the ruthless practices that Founder Del Vecchio in particular undertook to vertically integrate Luxottica’s manufacturing operations, acquire brands and retail operations to roll-up the eyewear industry. These practices were ruthless, impressive and well known within the industry.

Here is The Guardian in a must-read article on Del Vecchio’s sharp practices:

“Luxottica bought US Shoe for $1.4bn. Once the deal was done, Del Vecchio promptly broke up US Shoe, whose roots went back to 1879, until all that was left were the LensCrafters stores that he wanted in the first place, which he proceeded to fill with Luxottica frames. “That is exactly the formula they have used ever since,” said Jeff Cole, the former chief executive of Cole National Corporation, an even larger optical retailer that sold out to Luxottica in 2004. “When they buy a company, they spend a little time figuring it out and kick out all the other suppliers.”– Guardian ‘Long Read[4]’

So, we are not the first to notice the E-L’s market power. Indeed, there have been mutterings of price gouging in the eye care industry for some years now. The famous US TV show ‘60 Minutes’ (a vaguely similar show to ‘Panorama’) did a piece on how Luxottica has “cornered” the eyewear industry.[5] [6] For those concerned that prospective customers might be deterred by such negative publicity, we note that this show aired in 2013. We also note that Luxottica’s US retail operations last year were 32% higher at $5.7bn, five years on from that show. Any negative publicity from the show did not deter consumers one bit. It also did not stop the regulators approving the merger.

So how did the merger get approved? An in-depth interview[7] with Essilor’s the Head of Legal was very instructive to us in understanding the regulator’s focus and resulting assessment of the merger. In the interview the head lawyer laid out the key question that anti-trust regulators sought to answer (the so-called “theory of harm”) which was effectively:

Could Ray-Ban’s brand dominance allow the merged conglomerate to sell more lenses?

The key point, in determining the conclusion was that Ray-Ban was deemed a discretionary purchase, not a must-have. In theory, Ray-Ban sunglasses are not an essential purchase (unless you are in Top Gun!). The regulators took the view that this was essentially a fashion accessory business merging with a medical device business. The result of this approval is a much wider moat for the combined business.

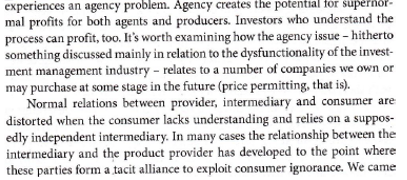

3. A word on agents

Howden Joinery and William Demant are examples of where agents are a very attractive part of the market dynamic. Our work on Howden Joinery (Holland Views – Howden, Double Agent, Dec 2016) highlighted the benefits that accrue to a company when an ‘independent’ agent is recommending the product. We included the following excerpt from the book Capital Returns where author Ed Chancellor outlines role of trusted intermediaries in influencing customer purchase decisions.

Source: Capital Returns book

Source: Capital Returns book

In the case of E-L it is the independent opticians (who are incentivised via loyalty and bulk purchase pricing to use E-L lenses and frames) who play this role. Better still in the customers eyes opticians are trusted quasi-medical professionals.

2. Secular Growth Tailwinds

In this section we make the following points:

- The historical growth record of both businesses has been strong albeit aided by significant acquisitions.

- Regarding future growth drivers, there is a Myopia epidemic globally, across both developed and developing markets

- Replacement cycles are also a key demand driver.

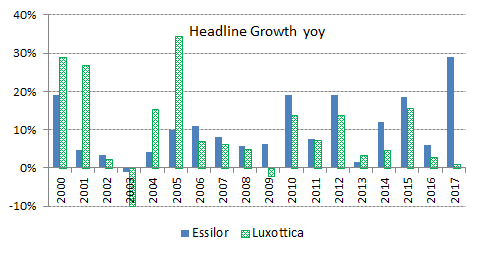

1. Growth track record

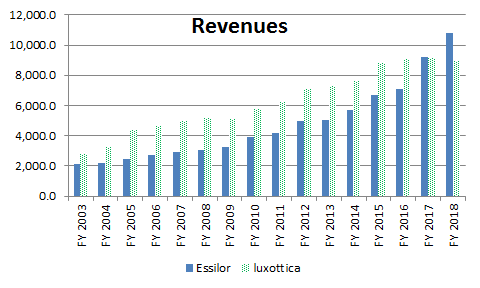

Fig.3 shows that both companies’ twenty-year track record growth have been strong. We fully realise that this has not been entirely organic as both companies, both for offensive reasons (Luxottica buying retail chains and brands) and defensive reasons (Essilor buying e-commerce brands). As a reminder, Essilor enjoys over 40% market share of global lenses sold and Luxottica dominates sun-glasses and high-end frame manufacture, distribution and retail with similar levels of market share.

Fig.3: Essilor and Luxottica standalone sales growth

Source: Bloomberg, Holland Advisors

Source: Bloomberg, Holland Advisors

2. Global Myopia

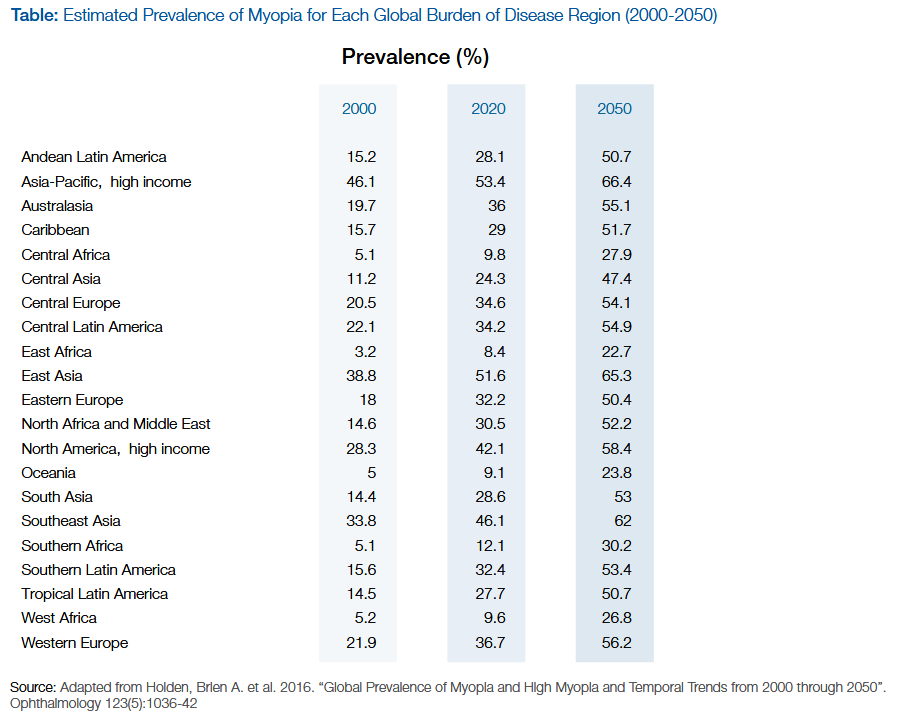

Despite the strong market share that E-L enjoys, the underlying eyewear market is both under-served and growing. This is due to widespread increased prevalence of short-sightedness (Myopia) across the world. Experts say that this is due to our increased time spent a) indoors and b) looking at computer screens. Eyewear is of course a market that first and foremost fills a medical need: Myopia and to a lesser extent other eye conditions such as glaucoma and cataracts. Fig.4 shows the growing prevalence of myopia across the world. This is a table worth studying in detail. Looking just at the developed markets expected myopia rates is instructive – with prevalence expected to rise 50% in Europe and North America alone between 2020 and 2050. Such forecasts have us thinking of snowballs on long wet hills!

Fig.4: Myopia prevalence

Source: WEF[8]

Source: WEF[8]

However, a large part of untapped demand will be in emerging markets and not all of these new consumers will be wearing Ray Ban or Prada frames. That said, new customers tend to be customers for life once they get on the corrective lens ‘ladder’. Both your authors have first-hand experience of this as we suspect do the majority of readers.

3. Replacement cycles

Eye tests are a key driver of replacement cycles. Capture rates (the clue is in the title) are typically 60% – i.e. 6 out of 10 eye tests typically lead to the purchase of new lenses and/or frames. Sunglasses, ostensibly a functional purchase are heavily influenced by fashion too. Bear in mind though, if you need prescription glasses, you also need prescription sunglasses. This excerpt from The Guardian long read piece sets out very well, the unusual scene that is the retail experience! It is this experience that makes the eyewear retail so resilient to disruption and only E-L to us looks like a complex monopoly even if regulators could not assess it as such.

“Buying them, in my experience anyway, is a fraught, somewhat exciting exercise that starts in a darkened room, where you contemplate the blurred letters and the degeneration of your visual cortex, and ends in a bright, gallery-like space where you enjoy the spry feel of acetate in your fingers, listen to what you are told, pay more than you were expecting to, and look forward to inhabiting a new, slightly sharper version of your existing self.” – Guardian Long Read

3. French-Italian Culture clash?

Since the merger was first announced in 2017, there has been much written about the managerial friction that ensued from the equal-merger of these two businesses. The story goes that Del Vecchio (now as 32% shareholder) will not agree to the composition of the top management of the merged business despite having agreed a merger agreement ensuring equal power between both sides until 2021. We offer some historical context which makes us more sanguine.

- We cannot read Leonardo Del Vecchio’s mind as to his attitude towards Essilor management, but we can be guided by his track record. He has always been highly rational with shareholder capital as it is his own.

- We also look at briefly Essilor’s culture. It does not have a founder at the helm but it is no shrinking violet. We ask, is it really that different a culture from Luxottica?

1. Leonardo Del Vecchio – pioneer, maverick and value creator

We think the merger with Essilor is a strategic finale for Del Vecchio, a legacy, for the 84 year old. Again we point to that Guardian long-read for anecdotes on Del Vecchio rise.[9] Having just read another book on Michael O’Leary – we see much similarity in these two exceptional businessmen. Both were completely ruthless in their capture of their chosen markets. Del Vecchio (DV) had two visionary insights with respect to the eyewear industry that he found himself in in 1961.

- DV, an Italian, understood the importance of design and that eyewear was, essentially a fashion accessory. He knew the value of good brands.

- DV, like Phil Knight who had a similar epiphany at Nike, realised that he needed to control the distribution of his products.

Luxottica’s acquisition of Ray-Ban was, with hindsight, genius, and the way that business was repositioned and its pricing power re-asserted would make Buffett smile. A former brand manager explained:

The first step in Ray-Ban’s turnaround was a comprehensive market research to identify the “DNA” of the brand. Luxottica shut down the manufacturing facilities and halted sales of the world’s most popular sunglasses brand for six months. Distribution was re-opened in a selective way, elevating the status of the brand. Manufacturing was transferred to Italy and prices were standardized across the world and went up from a minimum of $29 to a minimum of $89.”

The Luxottica playbook was clear:

“There is no competition in the industry, not anymore,” he told me. “Luxottica bought everyone. They set whatever prices they please.” – Former frame supplier to LensCrafter, Charles Dahan[10]

Luxottica’s last big acquisition was in 2007 when it paid c.€1.5bn for the Oakley sunglasses business. In 2006, the year before, Luxottica reported op income of c.€750m. Whereas by 2017, group operating income had grown to c.€1.3bn. Some of that growth was organic, some was store growth and some, it seems fair to us came from Oakley. It is hard as with all companies to dis-aggregate the returns from acquisitions but we think the fact that total group returns on capital (as per Fig.1) have been sustained through the periodic acquisitions points to a strong capital allocation record – we are happy to share our modelling on this.

2. Hubert Sagnières’ Essilor: a Wolf in sheep’s clothing?

Hubert Sagnières is an Essilor ‘lifer’, and became CEO in 2010 and presided over the negotiations with Del Vecchio for what was technically the take-over by Essilor of Luxottica. He is now Executive Vice Chairman of the merged entity. He is not an owner-manager like Del Vecchio but perhaps this is mitigated a little by the fact that Essilor employees owned 4% of the company prior to the deal.

The first few months post the merger have been marred by headlines suggesting much tension between the Chairman and Vice Chairman over the division of managerial responsibilities – what media deem be a battle for the balance of power at E-L[11]. We don’t have a strong view on the veracity or implications of this dispute.

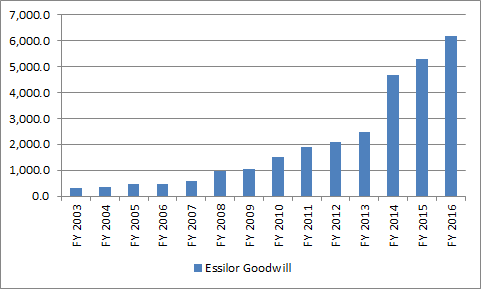

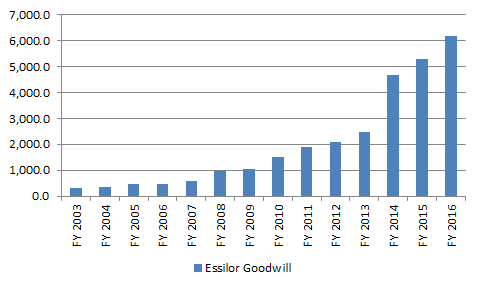

Perhaps more interestingly, under Sagnières’ watch (initially when he was Head of Europe and COO), Essilor spent €5.5bn on acquisitions since 2006. In an effort to assess how accretive those acquisitions were, here’s a thought process. In 2005, before this slew of deals began, Essilor’s operating income was c.€400m. A 15% annualised return on the €5.5bn spent equates to an incremental +€750m of operating income from the acquisitions. In 2017, Essilor actually reported €1,350m operating income. This suggests that the underlying operating profit growth was +$200m or 4% cagr. In other words, Essilor seems to be a good capital allocator too and has built scale and dominance.

Fig.5: Essilor has been rolling-up too – especially since 2006

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

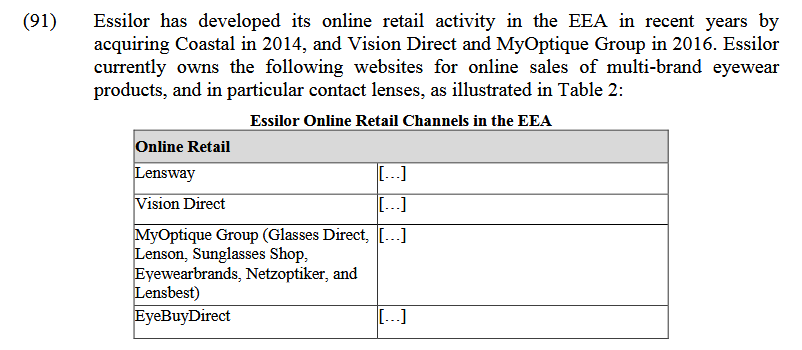

As a result of these acquisitions, Essilor owns a myriad of online retailers as the EU anti-trust investigation highlighted.

Fig.6: Essilor has recently been buying-up online eyewear businesses

Source: EU Commission

Source: EU Commission

“investment in in-store digitalization in order to enhance omni-channel strategy very well engage at Luxottica. Third, targeted partnership, such as the acquisition of Brille24, a leading online retailer on optical product in Germany, which are developing an interesting drive-to-store concept, who is participating ECPs to offer a mid-tier solution to consumer” – Laurent Vacherot, Deputy CEO, April 2019

Here’s another quirk that was noticed and examined by the FTC as part of their merger investigation. Vision Source is an alliance of US optometrists, a company setup to give independent eye care professionals (iECPs) the scale to negotiate and purchase supplies and technology (presumably to compete with the in-house chains owned by Luxottica and others). Actually, by scale, the combined size of its members’ retail outlets is second only to Luxottica in the US. Here’s the kicker though: Essilor acquired Vision Source in 2015!

We suggest that perhaps, the prevalent concern that the merger of these seemingly disparate companies is a massive culture-clash is actually lacking in substance? Both businesses seem very innovative (in technology and business practices) and notably just as aggressive as each other in the marketplace. It seems like a great fit to us, whoever ends up managing it.

4. By the numbers: a closer look at E-L track record

In this section we briefly look at:

- The historical financials of both E and L

- Competitor context such as European chains GrandVision and Specsavers

1. Historical E-L financials

Luxottica, as an independent company, compounded sales (including acquisitions) by c.7% since 2002 and Essilor, likewise, has grown revenues by c.11% cagr over the same period. We acknowledge that Luxottica’s headline growth in the last three years has been minimal with weak US store LFLs. However as we will show in this section, eyewear should remain a structural growth market – certainly in volume terms. Luxottica sold 83m frames in aggregate last year but the combination of retail and wholesale revenues means that it is impossible to calculate average wholesale pricing.

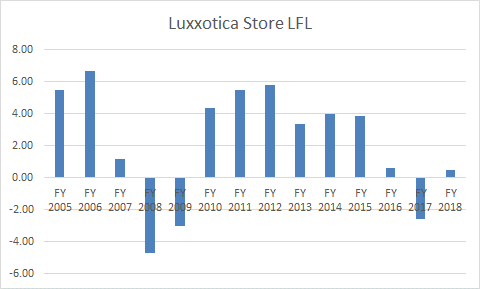

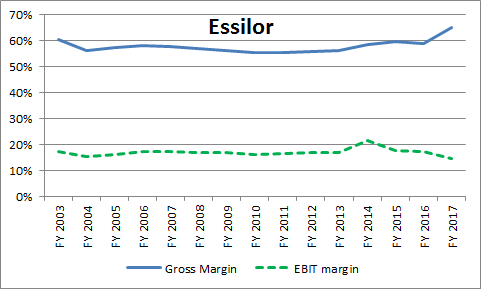

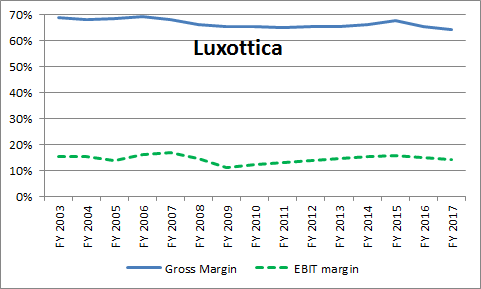

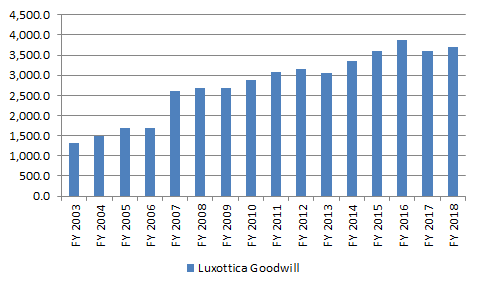

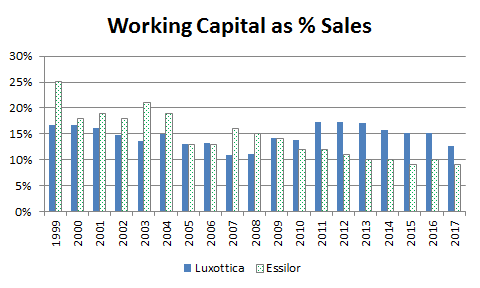

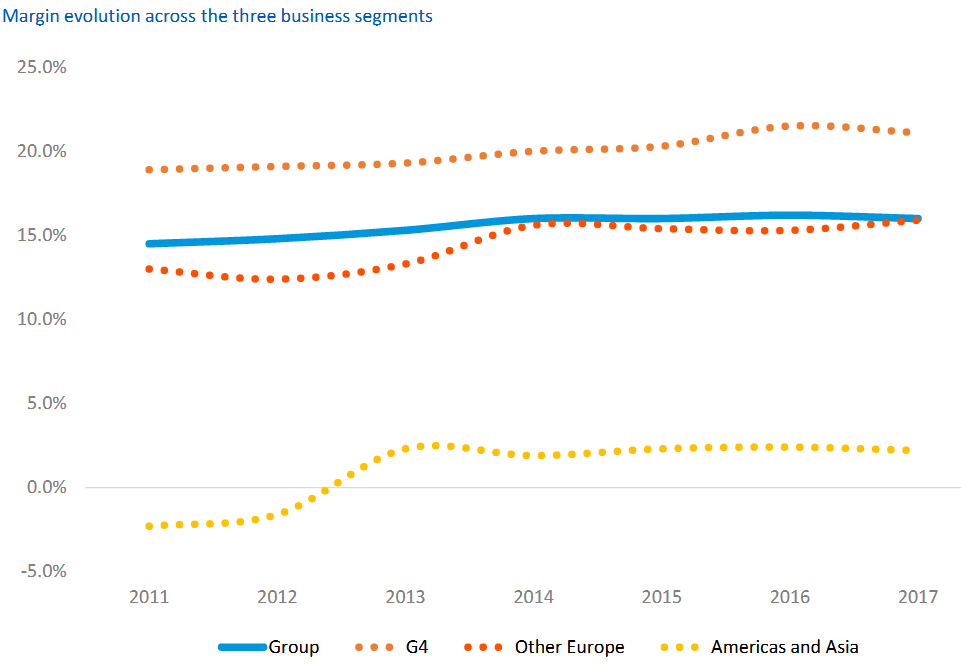

Fig.7 shows an array of charts from both companies’ history. Of particular note is:

- The growth track record of both businesses is excellent

- Though Luxottica store LFL sales have been cyclically weak since 2016

- That these are both very high (60-70%) gross margin businesses – in Luxottica’s case that includes a massive retail operation.

- E-L has excellent and stable operating margins, and especially as we show later in the context of European peers.

- We note also the reducing working capital needs (helpful to RoNTA and a low cost of growth)

Fig.7: E-L Chart book

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

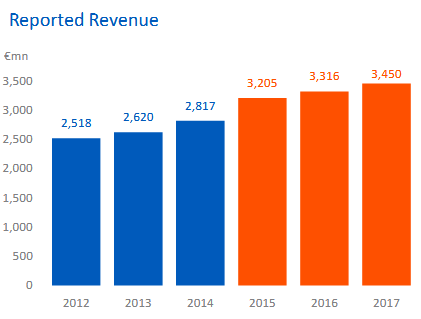

2. Other comparables

Fig.7b shows some data from GrandVision, the European based eyewear retailer that was spun-out of Dutch conglomerate HAL holdings a few years ago. In the UK, it owns the VisionExpress chain. Fig.7b shows a steady growth trend and perhaps more importantly, a margin of c.15%.

Fig.7b GrandVision

|

|

Source: GrandVision (parent of Vision Express et al)

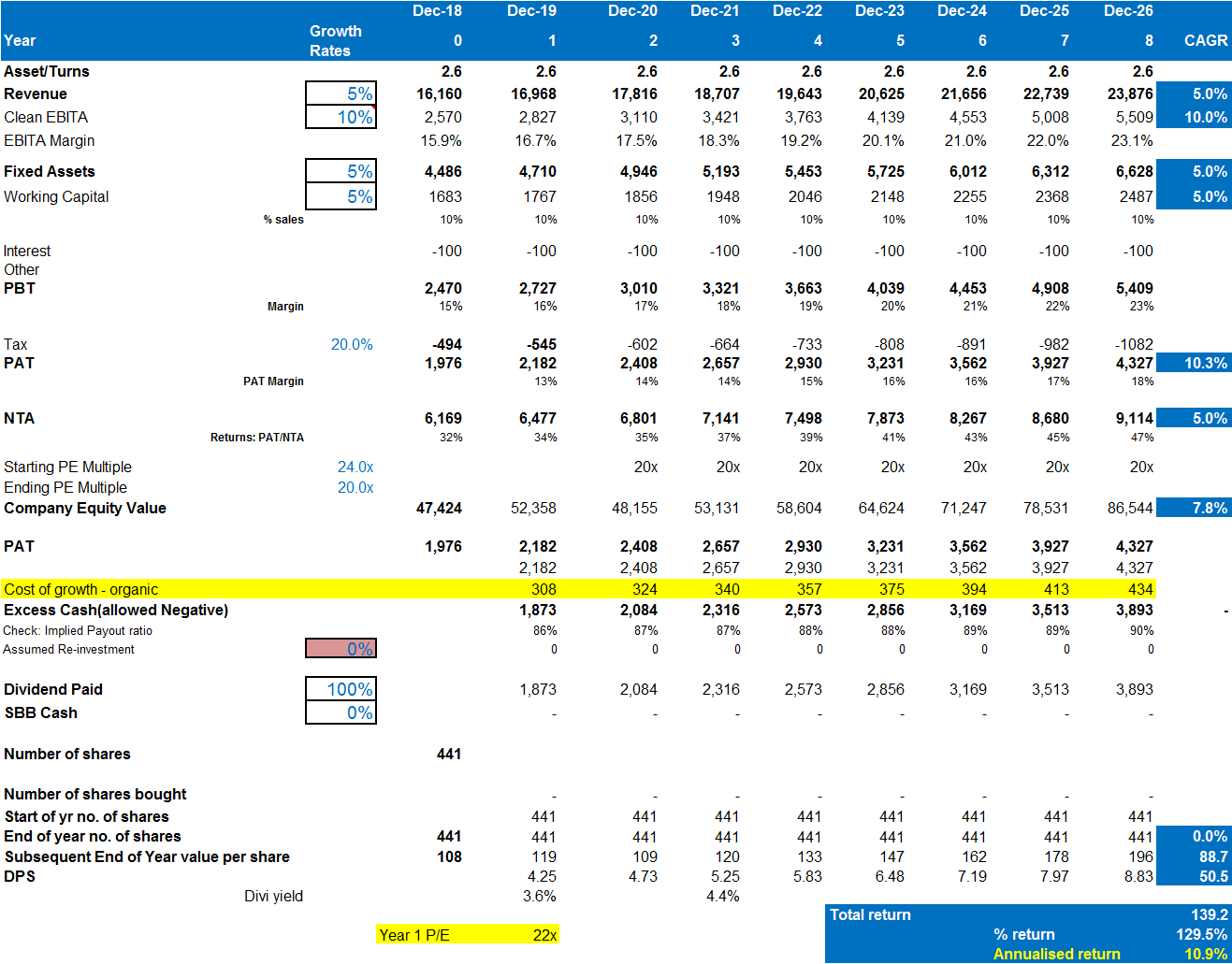

Specsavers needs no introduction but we thought its UK accounts might also give useful context. Specsavers caters more for the mass market ala GrandVision above, and thus does not really overlap with E-L’s target market per se but, considering the UK backdrop, its financials show that it is out-performing the UK high street in the last two years. Any UK retailer that is holding 6-7% operating margins in the last two years is operating in a resilient market we observe.

Fig.8: Specsavers – that rare beast – a resilient UK high street retailer!

Source: Companies House

Source: Companies House

5. Threats, Valuation and a conclusion

We conclude with three further areas:

- The elephant in the room is e-commerce and technology. We have looked hard at this. Can Amazon et al kill this business?

- We relay an insider’s view of the unique quirks of the eyewear market, the competitive landscape etc.

- In assessing the value on offer to an equity investor, we apply our own ‘compounding lens’ to it

1. Dollar Glasses Club?

Journalist: “what are your predictions for the future trend of this industry in the next few years?

Hubert Sagnières: “People will be able to take the eye exam with their smartphones.”

Is the internet a threat or a boon to EssilorLuxottica? Interesting question. If you Google “Ray-Ban”, a very impressive Ray-Ban e-commerce website emerges with, as you would expect, full purchasing capability in your country of origin. But are you really going to purchase a pair of high-end sunglasses without trying them on? Hardly.

So, the next question – is the product stock available online (both from the parent company and third party retailers) cheaper than in-store? Actually, no – and we have checked this. Our checks with opticians show that, like most luxury brands, Ray-Ban (i.e. Luxottica) is very careful to control pricing such that its retail customer base (again, in-house and external) are not disadvantaged versus the online retailers. We were told that Luxottica’s distributors perform checks on retailers to ensure that retail pricing matches company policy. If, as a retailer you try to discount stock to drive volume, you will lose favour and thus lose supply (Ref. SPD + Nike).

Dollar Shave Club (DSC) is a well-known start-up that successfully disrupted the lucrative razor market. It is a great example of a start-up business that used the power of online marketing platforms and online distribution to up-end the high margin razor blade business. MBA classes around the world are using DSC as a template to clone in other markets.

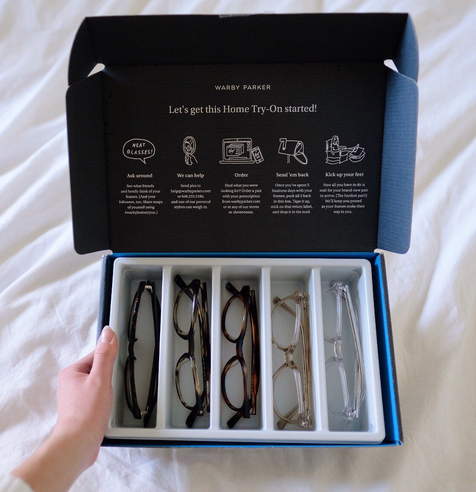

Inevitably, one such start-up is targeting the eyewear market: Warby Parker was setup by a three Wharton MBA grads in 2010. Its evolution suggests that the eyewear market might not be as easy to disrupt as other markets. Specifically, the business has seen the need for high street stores (it now has 90 stores) in addition to its e-commerce offering and obviously it does not enjoy the luxury brand names that remain licensed to the largest frame manufacturers. Our conclusion? The eyewear market might not be at all easy to disrupt, not least for the links opticians have with eye health and their quasi-medical responsibilities.

Sagnières’ quote above shows that this is something that Essilor is well aware of (as per our earlier analysis of its e-commerce acquisitions). We think camera technology will allow automated high quality refraction assessments in due course. Again though we come back to the nuance of the product, the need for fitting and personalisation (and Warby Parker’s 90 stores) as being a major impediment to the idea of an online challenge to the market.

The other important point to note re competition is the scale of the global market that is going to develop E-L looks to us perfectly placed to capture more than its fair share of that, but globally there will be plenty of demand to share out amongst existing and new players.

2. Confessions of an insider

In a bid to understand the nuances of the eyewear market, we found a talkative former insider with much credibility – Dean Butler. Butler setup LensCrafter in the US in 1983 (later acquired by Luxottica in 1995) and then moved to the UK where he setup Vision Express (sold to GrandVision), was on the board of glassesdirect.co.uk (sold to Essilor) and is recently an advisor to LensKart, an innovative optical retailer based in India. This man knows the eyewear industry.

In an excellent interview[12] from 2016, the out-spoken Butler makes some very revealing points:

- This is not a homogenous market. The multiples like Tesco make excellent money (“hand over fist”) in eyewear at what are very low price points. Butler said at the time that he’d love to own Tesco’s optical business (and a year later it was bought by Vision Express!).

The point is that eyewear is an attractive market across its various segments. The market is sufficiently wide and deep to allow the chains such as Tesco and Wal-Mart to co-exist with the high-end retailers and suppliers such as Luxxotica.

- Here is that price opacity again: “you can buy high quality lenses for 25p (yes that’s pence), and quality frames for £3 (i.e. wholesale), they’re not high style, but they’re not bad…its well known that Specsavers sell their frames to franchisees for £4-£6 each”. No wonder the MBA graduates are trying to disrupt the market.

- But brands matter: “and then in India, 5% of lenses sold are super-expensive £400 Japanese Tokay lenses that are so expensive they are not even sold in the UK”…i.e. counter-intuitively some of the less developed eyewear markets are more fashion/product quality conscious that the UK or US.

- “technology will disrupt this industry” (especially at lower end). Butler thinks that 25% of the market could move online. Refraction (simple vision tests) can be easily be automated Butler believed. But again, counter intuitively, Butler believes that e-commerce sales in India “is shortening replacement cycles”. This is an interesting point. 1) It shows the importance of getting prospective consumer ‘on the eyewear ladder’ and 2) it shows that eyewear as a fashion accessory is an important driver of demand – even, or perhaps especially in so-called developing markets.

- So why isn’t everyone doing it? i.e. disrupting/selling at really low prices, the interviewer asked?

Butler replies “cos there’s a part to the business that is a profession (optometry) and that is off-putting to a lot of entrepreneurs” (there’s that agent cropping up again!)

3. Valuation

“If you paid 20 times for a business that was compounding the economic value per share in the midteens and have some level of confidence it is likely to do that for a reasonably long level of time, you will get to heaven doing that.” – Chuck Akre

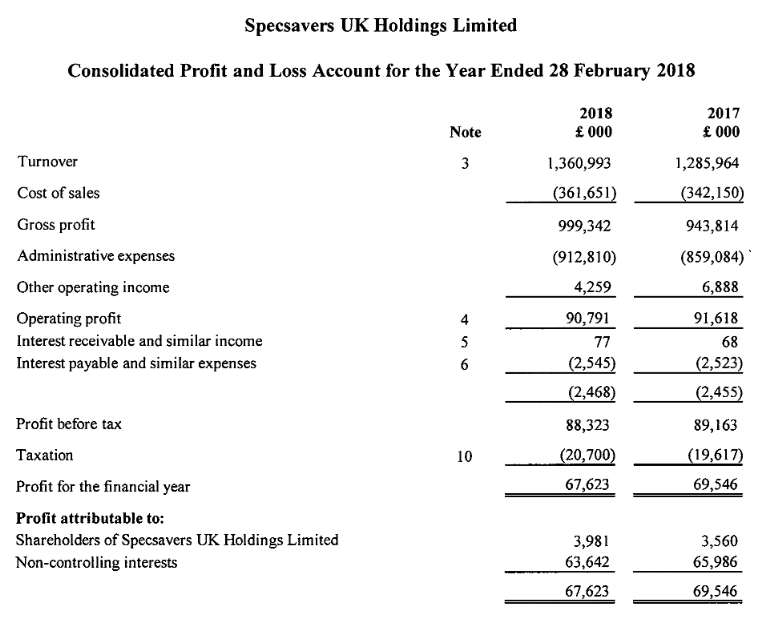

Firstly we make an assessment on E-L’s post-merger, post-synergies pro-forma earnings power and PE ratio. Fig.10 shows a very simplistic pro-forma P&L for the merged business.

Fig. 10: EssilorLuxottica pro-forma earnings power

Source: Holland Advisors

Source: Holland Advisors

Now, a c.21x adjusted PE is more than we have accepted as interesting in the past. Without consideration for the company, the multiple alone is discounting a better than good business. It is hard to argue that such a multiple is reflecting a stock that is out of favour (aka this is not a great company priced like a bad one).

However, before one dismisses what is a clearly, a high quality business because it is on c.21x PE, we suggest it is worth re-considering those high returns and the low cost of growth. It is via our growing understanding of compounders that we suggest such businesses should be analysed.

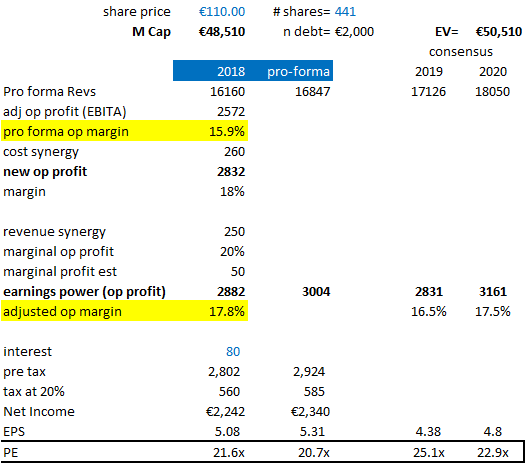

The bigger question is – is this business a compounder? If, so how might it compound? Simplistically, we think the newly merged business – as it stands today – could potentially deliver c.11% investor IRRs with plausible growth assumptions and a slight PE de-rating. We detail our assumptions in the Appendix (Fig.A).

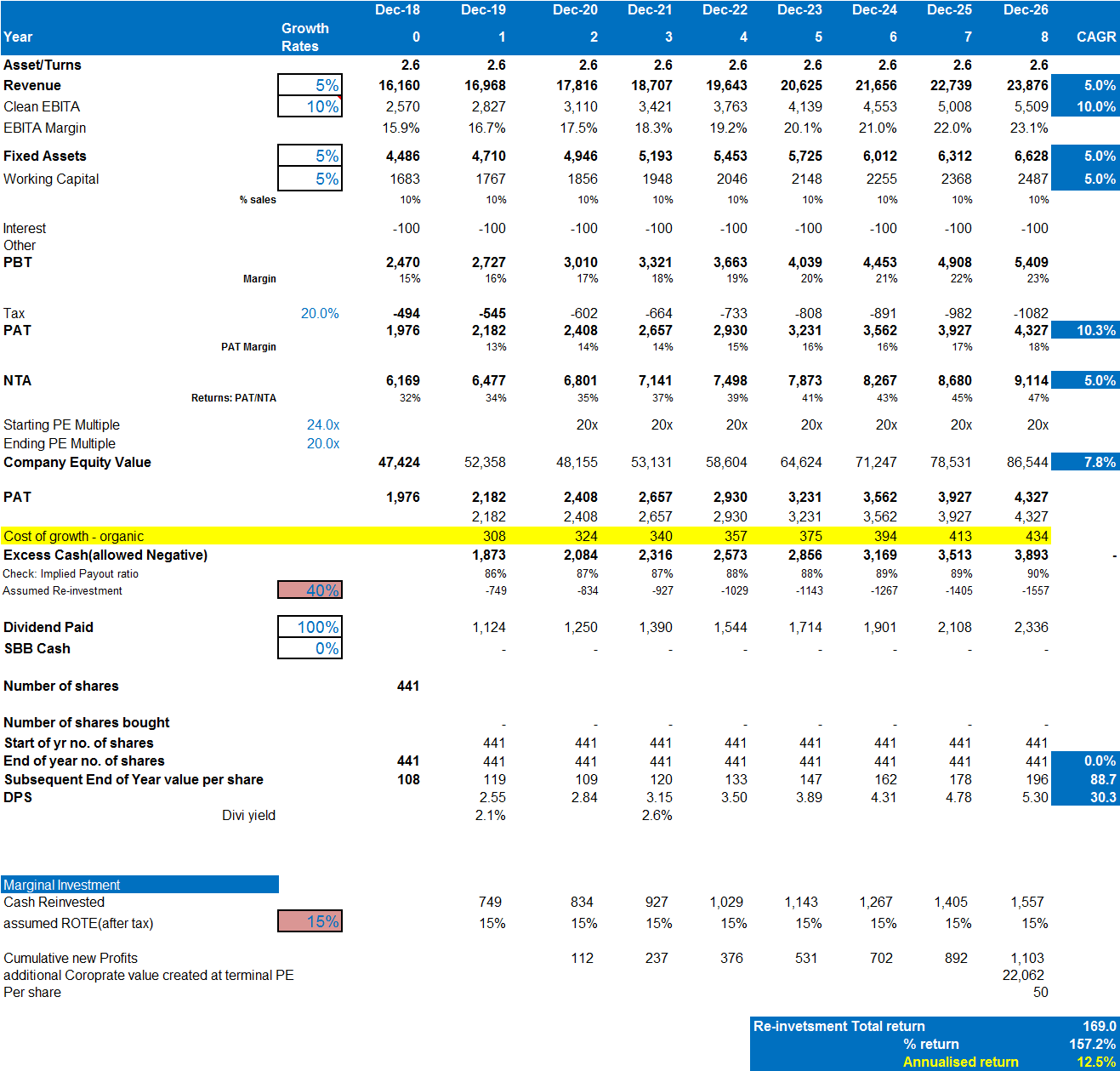

Businesses don’t stay in steady state of course and, it sounds it sounds like the business will remain an acquirer.

We anticipate that this (growth) will continue to increase as our bolt-on acquisition strategy is gaining momentum. And actually, in April, we already see an uptick here. Essentially, this is in relation to the acquisition that Laurent mentioned of Brille24 in Germany…as most people are aware, our M&A over the past couple of years has been quite moderate obviously with respect to the ongoing antitrust process. And so there is a robust pipeline that’s been put on hold, that’s now been fully reaccelerated, and we’ve seen that reacceleration start to come through in the first quarter of 2019.

And we continue to believe that it will continue to reaccelerate over the course of the year. And so, yes, there will be an acceleration in M&A-led growth coming through in 2019.” – Q1 19 conference call

On that basis, we take this into account in our compounding model. By assuming that say 40% of the excess cash from the core business as modelled above is reinvested (either in technology or say, Asian expansion). We assume that marginal returns on this investment are c.15%. Given historical marginal returns – this to us seems plausible. This combination of assumptions are of course crucial. If we can convince ourselves that this is a “invest more to make more” business then its compounding power could increase. Indeed were the 40% reinvested to make 15% pa as assured then our best guess investor IRR would rise from 11% to 13% (see Appendix Fig.B). We are not fools however. We know that many businesses make acquisitions at poor returns. However the odd industry where the scale monopoly player increases his reach and dominance by targeted acquisitions can create a more powerful beast. The track record of both companies increasing their dominance in this way is not something we should be too quick to dismiss.

Conclusion

We are drawn to EssilorLuxottica’s, excellent track record of growth and returns and its unique business model of vertical integration (brands, manufacturing and distribution). The future global industry growth we think is strong and secular. Demand is also relatively resilient due to its medical need, the role of professional intermediaries and the fashion element. All of these forces reinforce E-L’s excellent positioning. So the market outlook and the company’s position in it are excellent. Is it a cheap share? Ostensibly, no – the headline PE is punchy at c.25x. But that is before the merger synergies which seem likely to be delivered. Margin upside would also see another kicker to earnings in due course.

We started this work as the share price fell to c.€95, from which it has subsequently rallied 20%. We like the drivers for future growth we have found in E-L and our current best guess on likely investor IRRs (11-13%) we think is reasonable. At a lower starting valuation our pulses would race a little faster.

For choice we are buyers.

Andrew Hollingworth & Mark Power

The Directors and employees of Holland Advisors may have a beneficial interest in some of the companies mentioned in this report via holdings in a fund that they also act as advisors to.

Fig.A; Compounding Model – ‘Steady State’, 5% growth, op leverage, NO reinvestment

Fig.B; Compounding Model – 5% growth, op leverage, 40% of excess cash reinvestment

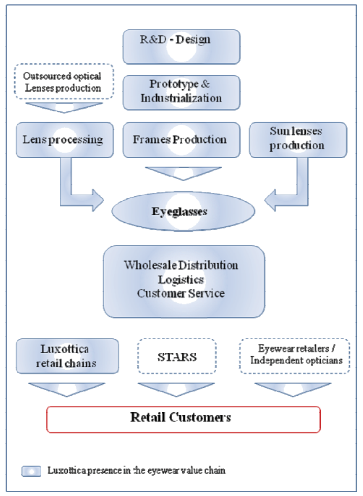

Fig.C: Luxottica (pre-merger) and the eyewear supply chain

Source: IMD case study

Source: IMD case study

Fig.D: Choices quotes from the industry

“Virtually every time something gets a big foothold in optometry, it screws us,” says Steve Nelson, OD. “That’s true whether it’s Luxottica or VSP. They virtually all start out as a ‘partner to optometry’ and all end up getting too large to be a good partner to us and end up with a business model using optometry to generate huge profits.At that point, we are too invested to back away and we just have to take it. I’m not saying this will screw us because maybe this time will be different, but history certainly suggests we should view this with a fair measure of scepticism”[13]

““We need to be open-minded and never assume that we have arrived, looking at the world as our only point of reference. We need to know how to enter the market and remain firmly there, changing, innovating and constantly improving, while preserving our DNA and our fundamental characteristics.”” – attributed to Leonarado Del Vecchio, founder of Luxottica

Fig.E: ‘The Dollar Shave Club of’ glasses? Warby Parker

Source: Fortune magazine

Source: Fortune magazine

Disclaimer

This document does not consist of investment research as it has not been prepared in accordance with UK legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research. Therefore even if it contains a research recommendation it should be treated as a marketing communication and as such will be fair, clear and not misleading in line with Financial Conduct Authority rules. Holland Advisors is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. This presentation is intended for institutional investors and high net worth experienced investors who understand the risks involved with the investment being promoted within this document. This communication should not be distributed to anyone other than the intended recipients and should not be relied upon by retail clients (as defined by Financial Conduct Authority). This communication is being supplied to you solely for your information and may not be reproduced, re-distributed or passed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose. This communication is provided for information purposes only and should not be regarded as an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any security or other financial instrument. Any opinions cited in this communication are subject to change without notice. This communication is not a personal recommendation to you. Holland Advisors takes all reasonable care to ensure that the information is accurate and complete; however no warranty, representation, or undertaking is given that it is free from inaccuracies or omissions. This communication is based on and contains current public information, data, opinions, estimates and projections obtained from sources we believe to be reliable. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance. The content of this communication may have been disclosed to the issuer(s) prior to dissemination in order to verify its factual accuracy. Investments in general involve some degree of risk therefore Prospective Investors should be aware that the value of any investment may rise and fall and you may get back less than you invested. Value and income may be adversely affected by exchange rates, interest rates and other factors. The investment discussed in this communication may not be eligible for sale in some states or countries and may not be suitable for all investors. If you are unsure about the suitability of this investment given your financial objectives, resources and risk appetite, please contact your financial advisor before taking any further action. This document is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as an offer or solicitation to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned in it. Holland Advisors and/or its officers, directors and employees may have or take positions in securities or derivatives mentioned in this document (or in any related investment) and may from time to time dispose of any such securities (or instrument). Holland Advisors manage conflicts of interest in regard to this communication internally via their compliance procedures.

- “Luxottica is the largest optical retailer in the United States, with LensCrafters and Pearle Vision stores and optical retail concession operations in Target and Sears stores. It currently competes to varying degrees against iECPs, other optical retail stores, and “big box” retailers, among others. It is also the second-largest managed vision care provider in the United States” source: FTC https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/closing_letters/nid/1710060commissionstatement.pdf ↑

- ↑

- http://www.luxottica.com/en/eyewear-brands ↑

- https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/may/10/the-invisible-power-of-big-glasses-eyewear-industry-essilor-luxottica ↑

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDdq2rIqAlM ↑

- ‘Sticker Shock: why are glasses so expensive’ https://www.cbsnews.com/news/sticker-shock-why-are-glasses-so-expensive-07-10-2012/ ↑

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ul_2YSjTv8w ↑

- http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_2016_EYElliance.pdf ↑

- https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/may/10/the-invisible-power-of-big-glasses-eyewear-industry-essilor-luxottica ↑

- https://www.latimes.com/business/lazarus/la-fi-lazarus-glasses-lenscrafters-luxottica-monopoly-20190305-story.html ↑

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-essilorluxottica-governance-sagnieres/essilorluxotticas-sagnieres-hits-back-at-attack-from-del-vecchio-idUSKCN1R21B5 ↑

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKqcY3d-fbg ↑

- https://www.optometrytimes.com/practice-management/what-essilor-vision-source-deal-means-you ↑